THE SILENT SOUL

- Anthony Xiradakis

- Dec 26, 2025

- 2 min read

THE SILENT SOUL

When the Object Becomes the Hero

By Anthony Xiradakis

Cinema sometimes performs a quiet miracle: it turns the inanimate into the most alive presence on screen. Not through gimmickry, but through a deeper operation—one that exposes how humans attach destiny, memory, and meaning to the things that surround them. In certain films, the true protagonist does not breathe, speak, or bleed. It simply is—and that stillness becomes its signature.

Consider The Red Balloon (Albert Lamorisse). A single scarlet sphere drifts above postwar Paris and becomes far more than a playful object. It embodies absolute freedom: a refusal of gravity, an escape from social constraint. The child appears to chase it, yet the story’s secret inversion is clear—the balloon guides, chooses, initiates. The boy follows. The object leads. What should be passive becomes willful, almost sacred, and the human character turns into a satellite orbiting a silent center.

A similar transmutation unfolds in Up (Pete Docter), where an ordinary chair—simple wood and fabric—contains an entire marriage. It is not merely furniture but a sanctuary of absence, a reliquary of love. Carl’s journey is outwardly geographic, yet spiritually it returns again and again to what that chair represents: the weight of memory, the ache of the empty place, the slow learning of acceptance. The object gathers a lifetime into a single, immobile form.

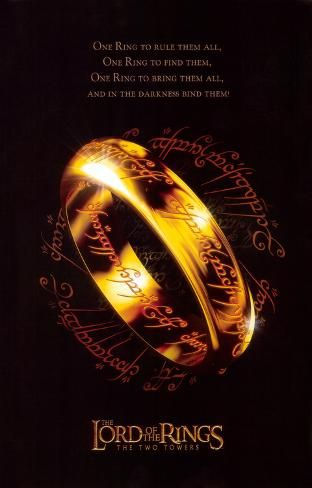

Then comes the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings (Peter Jackson), where the object-hero expands to cosmic scale. The Ring is not a symbol of corruption—it behaves like corruption itself: seductive, strategic, parasitic. Frodo carries it, but the film constantly asks the darker question: who is truly carrying whom? The artifact seems to possess intention, and the “heroes” often resemble pieces moved across a board the object has already designed.

Why are objects so potent on screen? Because they hold a decisive dramaturgical advantage: silence. They signify without explaining. They speak without language. That muteness forces the viewer into participation—projection, interpretation, completion. A talking character belongs to a culture and a moment; a silent object crosses languages and centuries. The red balloon can move a Parisian child of 1956 and an adult viewer decades later with the same immediate clarity, as if it addressed something pre-verbal and archetypal in us.

Objects also function as memory engines. They are time made tangible—what philosophy describes abstractly, cinema renders visible. A worn chair can contain fifty years. A ring can carry millennia. A balloon can hold the whole eternity of childhood inside a fragile sphere. And precisely because objects are materially vulnerable—easily broken, burned, lost—their destruction strikes with unexpected force. We grieve not for “things,” but for what we have poured into them: promises, identities, tenderness, the proof that something mattered.

In the end, the object-hero reveals a double truth. It shows how cinema works—through symbolic concentration and emotional projection—and it shows how we work, too. We live among artifacts that quietly shape our inner life. A favorite pen, a chipped mug, a watch inherited: each could be the center of an intimate epic. Films that animate objects do not escape reality; they re-enchant it, reminding us that matter is never merely matter when a human heart has touched it.